Happy Holidays

" In this universe the night was falling; the shadows were lengthening towards an east that would not know another dawn. But elsewhere the stars were still young and the light of morning lingered; and along the path he once had followed, Man would one day go again"

Arthur C. Clarke Against the Fall of Night

Saturday, December 21, 2019

Sunday, November 10, 2019

Saturday Reading; Stableford, Moorcock, Harrison, Davis

This story concerns the first Apollo landing on the moon. During the initial exploration, one of the astronauts Glazer falls into a crevasse concealed by the thick coating of dust. His companion Gino Lombardi tries to rescue him but is unsuccessful. Gino then completed his assigned work and contacted the pilot of the orbiting ship Danton Coye.

"Glazer is dead. I'm alone. I have all the data and photographs required. Permission requested to cut this stay shorter than planned. No need for a whole day down here." (165)

Gino's somewhat callous response could be dismissed as the result of shock. He does break down later on the ship back to Earth, but the reaction concerning Glazer's death does indicate a problem I had with the entire story. The dialogue, the description, just seemed flat, unemotional and unembellished.

The story itself gets rolling when they return to Earth and find themselves in an alternate timeline. The story was okay, the most interesting part for me occurs when Albert Einstein, still alive in this timeline offers them a cure for some of the worse cancers in exchange for weapons to use against the Nazis. Still not an auspicious start, but Harrison has a huge body of work, and this collection alone covers 50 years.

Nest I decided on some more Moorcock, I read "The Jade Man's Eyes", one of his stories about Elric of Melniboné. " Elric is the last emperor of the stagnating island civilization of Melniboné. Physically weak and frail, the albino Elric must use drugs (special herbs) to maintain his health."

I have read several of Moorcock's Eternal Champion stories in the past. Most recently, I have been reading the stories of Dorian Hawkmoon, Duke of Köln. I am finding the Hawkmoon stories quite formulaic and the character one dimensional. Elric was much more interesting in part because he is unpredictable. His magical broadsword Stormbringer is often uncontrollable, and his demonic patron, Arioch unreliable. In this story, Elric and his companion Moonglum are enlisted by the noble Duke Avan Astran to accompany him on a treasure-hunting expedition to the ancestral island of Elric's people. This type of quest is a staple of the sword and sorcery set, but I found Moorcock's a step above. The threats and responses were more interesting; the pacing moved the plot along without rushing.

Also, Moorcok's style reminds me of some of my favourite fantasists like Eric Rücker Eddison, Lord Dunsany, Clarke Ashton Smith and Robert Howard.

" It happened that one springtime two strange men came to Chalal. They rode their weary Shazaian horses along the quays of marble and lapis lazuli beside the fast-flowing river. One was very tall, with a paper white skin, crimson eyes and hair the color of milk, and he carried a huge, scabbarded broadsword at his side." (57)

or

"One of those legends speaks of a city older than dreaming Omrryr." (61)

Moorcock is quite honest about his influences in creating the character of Elric of Melniboné; they seem quite wide-ranging; his comments appear here.

As I said earlier, Moorcock's Eternal Champion interests me, and I will be exploring it and Elric in greater detail.

Joachim Boaz at Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations mentioned he had obtained a copy of the anthology Orbit 11.

One of the stories mentioned on the back caught my attention.

"TO PLANT A SEED. Is many really master of the Universe? In this brilliantly conceived story, an incredible project is launched to preserve the human race—not only from the death of Earth’s sun billions of years in the future… but from the ultimate collapse of the entire Universe itself!"

Since I had the book, I read the story by Hank Davis. Two scientists Cullins and Cain, are seeking funding for a seed ship. Using a McJunkins Field, which slows time, they will encase a spaceship containing human volunteers. The humans will not age within the field. The plan is that they will remain in stasis as the universe winds down and collapses. Then, when the next big bang occurs, they can seed the new universe with humans. (Characters in the story do mention how wrong this is.) This story could have been interesting, but it isn't. It interspersed the action, such as it is, with transcripts, news feeds and exchanges taking the form of questions and answers between characters with an omnipresent viewpoint concerning the activities of Cullens and Cain. There was little character development, but a fair bit of technical explanations/lectures, some reminded me of high school math. The main problem is that it is incredibly sexist bordering on hateful. Most of it is directed at Cullin's girlfriend, Erika. Cain does try to date one of his female colleagues, but she is never named. Oddly, Davis invests so much space in a short story in underscoring the misogyny of his central characters. I am in no hurry to read more by him.

I like Brian Stableford. I covered his story "The Growth of the House of Usher here."

I enjoyed the first novel of his Hooded Swan collection and hope to cover the entire series at some point. I also want to post on Sherlock Holmes and the Vampires of Eternity for my HPL blog but the length makes it a bit daunting. I have also purchased a number of his translations of early french science fiction/roman scientifique.

So when I noticed Journey to the Center on a trip to the basement yesterday, I picked it up. Michael Rousseau is a freelance scavenger on the planet Asgard. The planet is controlled by a humanoid race called the Tetron. However, a number of other races, including Terrans, live there. The planet lost its atmosphere in the distant past. The native race burrowed into the surface then disappeared, leaving behind many uninhabited levels. The alien races on Asgard explore these levels looking for artifacts they can sell. There are two groups the Consolidated Research Establishment composed of many races who work in a highly structured manner. Then there are freelancers, both groups and individuals like Rousseau. Rousseau's problems begin when the Tetron Immigration Authority contacts him, asking that he show a new earth immigrant the ropes. This is a common practice on Asgard members of one race are asked to look after new members of the same race. Rousseau is due to leave on a scavenging trip and suggests his friend Saul Lyndrach to look after Myrlin the new arrival. Then things go south Saul and Myrlin disappear, and Rousseau is framed for murder by Amara Guur, the criminal kingpin on Asgard. Under Tetrax law, criminals are sold into contact slavery. Guur wants Rousseau to lead an expedition into the planet.

But before Rousseau can sign the documents, Starship captain Susarma Lear and her stormtroopers show up and conscript Rousseau. The Terrans have just won a vicious war (about which Rousseau knows virtually nothing) in which they basically wiped out another species. Now the war is over, and there is only one loose end. Myrlin is not human but an android created by the enemy, and they have to kill him. And all this occurs by page 47.

I love this stuff. We have anthropology with Rousseau's Tetrax lawyer explaining that contract slavery is the highest form of civilization, higher even than capitalism because it controls the efforts of so many individuals. We have interesting descriptions of the planet and the possible explanations for its current state. There is a nod to a panspermia explanation for the races we see on Asgard. There is a nearby Black Galaxy (dust cloud), which will eventually cover most of the spiral arm. Is Asgard a small Dyson sphere that was built first and then had a small sun ignited inside? Is Asgard a ship that transported its population out of Black Galaxy? Using Rousseau Stableford is obviously playing with lots of ideas, and I enjoyed all of it. He also packs a lot into 153 pages. Rousseau is a very stereotypical loner/rebel found in SF. Still, here he is an excellent foil to the "starship troopers" (Stableford's actual term to describe the soldiers that accompany Lear). That said Lear is not a cardboard martinet, she is a strong, smart capable woman, nice to see in SF. I also enjoyed the resolution.

Stableford dedicated "For Lionel Fanthorpe-a kindred spirit" Fanthrope was the leading light of Badger Books.

In his work Stableford explores biology, biotechnology, big dumb objects and a mixture of ideas from roman scientifique, the planetary romance and even the weird tale. I find this a nice change from the libertarian mechanistic focus of much science fiction. In this book I even see hints of Frankenstein. There are two more Asgard books, and I will definitely track them down.

Cover credits

Harrison; cover design Shelly Eshkar cover ill. Vincent di Fate

Flashing Swords 2; Bruce Pennington, I always enjoy his work

Orbit 11; Paul Lehr another favourite

Journey to the Center; Jim Yost

Sunday, November 3, 2019

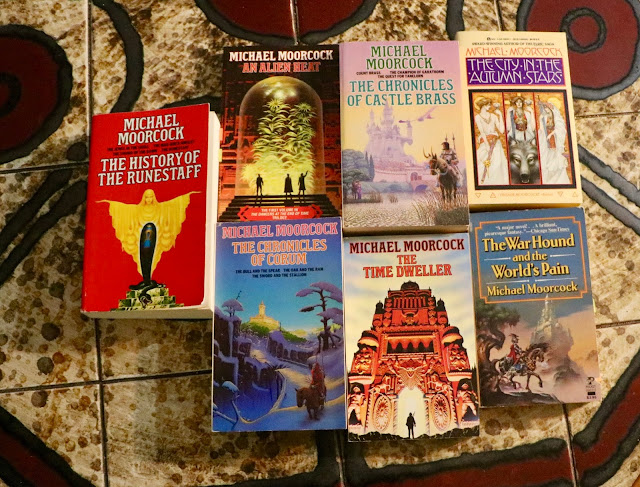

New Arrivals; Moorcock Moorcock The War Hound and the World's Pain

I have been going to a new bookstore in Calgary's Inglewood neighbourhood, Next Page is a branch of the independent bookstore Pages. They sell both new and used books. While the selection of used science fiction is quite limited I have found more than enough to decimate my budget. The books are in beautiful condition with a nice selection of NA and UK publishers and authors. This represents the booty from several visits.

As always I love old science fiction, I am also a bit of an anglophile so Doyle, Well and Jefferies were a welcome find. I am also a big Hesse fan I read them to relax, often skipping here and there.

I read Bear's short story "Blood Music", it was quite good. I always wanted to try the novel version. Do I need more Clarke and Asimov, no. Could I resist new editions of their short stories. No, I find it difficult.

I am familiar with Micheal Moorcock's writing primarily from the various series that form The Eternal Champion multiverse. Initially I did not plan on buying these books. His sword and sorcery novels had been formulaic and I was torn. However I had also read his novella "The Wrecks of Time" in New Worlds and I had purchased Colin Greenland's The Entropy Exhibition on Moorcock's tenure at New Worlds. We were waiting for friends and the longer we waited the more titles I grabbed. I am glad I did. I have actually ordered some of his older works to complete series I already owed.

I am not going to attribute all the covers in this post, You can find this information at the isfdb. I will do this if I deal with a work in greater detail.

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/index.cgi

Cover by Boris Vallejo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirty_Years%27_War

The wikipedia entry on Moorcock notes:

"Moorcock's works are noted for their political nature and content. In one interview, he states, "I am an anarchist and a pragmatist. My moral/philosophical position is that of an anarchist."[16] Further, in describing how his writing relates to his political philosophy, Moorcock says, "My books frequently deal with aristocratic heroes, gods and so forth. All of them end on a note which often states quite directly that one should serve neither gods nor masters but become one's own master."{16) "

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Moorcock

The fantasy settings that Moorcock creates often include the negative treatment of female characters. This should of course, not be considered a reflection of his beliefs. Moorcock stated in an interview in the Guardian that he fell out with one of his closest friends the writer J.G. Ballard.

"We were estranged for some time because of his

treatment of women. I got sick of it."

No stranger to censorship himself the quote below is also interesting.

I found The War Hound and the World's Pain an interesting read. As is often the case with Moorcock there is a sequel, The City In the Autumn Stars, pictured above, which I have not yet read. I am going to be reading more Moorcock for a number of reasons. His work in the field especially with New Worlds make him a influential figure in science fiction. He was prolific which means there are lots of novels and stories to choose from. If like me, you enjoy seeing how an author's themes and plots change over time this can be quite attractive. He crosses genre which I like mixing elements of both science fiction and fantasy in wide ranging works that vary from fairly standard sword and sorcery to the adventure of the hipster Jerry Cornelius. And I have enjoyed his work in the past. What do you think of Moorcock's work.

"Science fiction/fantasy author Michael Moorcock has suggested that the Gor novels should be placed on the top shelves of bookstores, saying, "I’m not for censorship but I am for strategies which marginalize stuff that works to objectify women and suggests women enjoy being beaten."[17]"

I found The War Hound and the World's Pain an interesting read. As is often the case with Moorcock there is a sequel, The City In the Autumn Stars, pictured above, which I have not yet read. I am going to be reading more Moorcock for a number of reasons. His work in the field especially with New Worlds make him a influential figure in science fiction. He was prolific which means there are lots of novels and stories to choose from. If like me, you enjoy seeing how an author's themes and plots change over time this can be quite attractive. He crosses genre which I like mixing elements of both science fiction and fantasy in wide ranging works that vary from fairly standard sword and sorcery to the adventure of the hipster Jerry Cornelius. And I have enjoyed his work in the past. What do you think of Moorcock's work.

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

Boo!!

De Plancy’s Dictionnaire infernal respectively characterizes these demons, in the words of an unknown translator, as “the one who glistens horribly like a rainbow of insects; the one who quivers in a horrible manner; and the one who moves with a particular creeping motion.”

Songs of a Dead Dreamer

Thomas Ligotti

Sunday, October 13, 2019

Installment Plan by Clifford Simak

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I declared The Summer of Simak, collected some materials, and then made very little progress. One problem was that I did not initially know where to start. Then when, how much reading, research and writing should I do in preparation. I could not blindly jump in, could I? I have read Simak all my reading life, but only touched a portion of his oeuvre. I only remember a much smaller subset that I could hope to cover without extensive rereading. After looking at what I have read, what I remember. I began to ask myself have I read critically enough to do Simak and any potential readers of my blog justice.

I considered doing, or claiming, to do a close reading of Simak whatever that means. So I looked up some online lesson plans on close reading, and two things occurred to me. I do not know enough about literary analysis to know if Simak’s works lend themselves to this approach or if I could do a credible job. It also reminded me of the sterility of the university English courses I took where the significance of the work paled when faced with the great amorphous mass of scholarship that already existed, even more importantly, what the professor thought of it. Eventually, I realized that the whole accretion of theory, existing criticism, literary schools, both political and sociological, and personal bias meant that reading the actual work and forming an impression of it would hinder me in the course. I did not want to travel that road yet again,

I chose Simak because I like his work, or lots of it and posting about it forces me to approach the work on a deeper level. A bit of research, some middling thought and an attempt to read more of his work systematically seem to be good enough goals for my advancing years. I am still reading Simak and science fiction, in general, to see different perspectives, to experience fictionally, different realities. I read it to participate in the author’s thought experiments about the future of technology and humankind in general. I also seek wonder and to be entertained. Possibly, occasionally, something I read may even change me or my opinions in some fleeting way. Reading and writing about the works of Clifford D. Simak will be, in my mind, a labour not of scholarship but love.

One step I took was to buy all 12 volumes of The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak. As the Black Gate website notes when discussing the first volumes.

"All three, like all six volumes announced so far, are edited by David W. Wixon, the Executor of Simak’s Literary Estate. Wixon, a close friend of Simak, contributes an introduction to each volume, and short intros to each story, providing a little background on its publishing history and other interesting tidbits."

"As a special treat the first volume, I Am Crying All Inside, includes the never-before-published “I Had No Head and My Eyes Were Floating Way Up in the Air,” originally written in 1973 for Harlan Ellison’s famously unpublished anthology Last Dangerous Visions, and finally pried out of Ellison’s unrelenting grip after 42 very long years."

https://www.blackgate.com/2015/10/14/future-treasures-the-complete-short-fiction-of-clifford-d-simak-volumes-1-3/

It appears there might be a couple more volumes in the future. I have found Wixon's introductions quite useful. The introduction to each volume looks at another aspect of Simak' s work, for example, his westerns, his non-fiction books, etc.

I think overall this project (like my stalled look back at Frank Herbert) will take much longer than intended. But let's get started. Despite planning this project for some time, I have chosen to begin with three stories that were not in my plans, none of which I had read previously. (I read them and they basically self selected) I had planned to start with his novel Cosmic Engineers. However, taken together, these stories do provide a good overview of trends and outliers within Simak's work. I will cover the first "Installment Plan" in this post. Discussions of "Worlds Without End" and "The World That Couldn't Be" will follow.

"Installment Plan" first appeared in Galaxy Magazine, February 1959. (cover by Emsh, interiors by Wallace Wood ) It also appears in I Am Crying All Inside and Other Stories vol. 1 of the Complete Short fiction series.

Steve Sheridan is the supervisor of a crew of robots on a trade mission to Garson IV. Garson IV was first visited by staff from Central Trading 20 years ago. At that time they discovered a tuber with medicinal properties.

"From the podar, the tuber’s native designation, had been derived a drug which had been given a long and agonizing name and had turned out to be the almost perfect tranquilizer. It appeared to have no untoward side-effects; it was not lethal if taken in too enthusiastic dosage; it was slightly habit-forming, a most attractive feature for all who might be concerned with the sale of it. To a race vitally concerned with an increasing array of disorders traceable to tension, such a drug was a boon, indeed. For years, a search for such a tranquilizer had been carried on in the laboratories and here it suddenly was, a gift from a new-found planet."

"Installment Plan"

A second expedition encouraged the Garsonians to raise podar and to store it, for some reason, in red New England style barns. Central Trading then spent years trying to synthesize the drug or raise podar on planets they control. They have been unsuccessful so Sheridan has been sent to trade for the crops that have been stored. However the expedition gets off to a rocky start. One of the cargo floaters crashes damaging a number of the robots. This accident introduces two elements. One is robot names in Simak's stories.

In Vol 6 New Folk's Home Wixon discusses how Simak often uses biblical names for his robots. "Two aspects of the names Cliff used will certainly be familiar to his readers. First, many—though not all—of his robots bore biblical names: Nicodemus, Ezekiel, Gideon, Abraham. "

Here we have a Hezekiah, Gideon Lemuel and Abraham etc. there is also Maximilian and Napoleon.

Also Sheridan has a number of transmogs which allows him to reprogram the skill sets of the robots, (their base personality does seem to remain the same). This become quite important when a cargo sled crashes damaging a number of the robots. To repair the damaged robots Sheridan equips three robots with roboticists transmogs. Other transmogs that we encounter or that are mentioned are spacehand, missionary, semantics, playwright, public speaker, auctioneer, lawyer, doctor etc. Indeed the robots handle most of the work including planning for the mission. However Sheridan notes robot crews have demonstrated in the past that they cannot operate successfully on their own without at least one human supervisor. That said robots are crucial to mankind's expansion into space.

"no ship that could carry more than a dribble of the merchandise needed for interstellar trade. For that purpose, there was the cargo sled. The sled, set in an orbit around the planet of its origin, was loaded by a fleet of floaters, shuttling back and forth. Loaded, the sled was manned by robots and given the start on its long journey by the expedition ship. By the dint of the engines on the sled itself and the power of the expedition ship, the speed built up and up. There was a tricky point when one reached the speed of light, but after that it became somewhat easier—although, for interstellar travel, there was need of speed many times in excess of the speed of light. And so the sled sped on, following close behind the expedition ship, which served as a pilot craft through that strange gray area where space and time were twisted into something other than normal space and time. Without robots, the cargo sleds would have been impossible; no human crew could ride a cargo ship and maintain the continuous routine of inspection that was necessary."

"Installment Plan"

The real problems occur when Sheridan and his crew attempt to trade with the Garsonians. Despite the fact that there are fields of what appears to be podar the natives deny they grow it any longer. They also claim that the barns, which are sealed are empty. Crews on trade missions are forbidden to use any violence against native populations so breaking into one is not an option. Sheridan and the robots do note changes from the observations of previous expeditions. The native villages are unkempt, once described as happy go lucky the native seem stressed, tired and generally unhappy. They obviously want the items on offer but will not trade for them. The robots then come up with a number of strategies to attempt to change their minds including stand-up comedy and medicine shows but are unsuccessful. The mystery when solved is not a happy one.

This was a great place to start my review of Simak for a number of reasons. One there was more of a focus on an alien planet and culture that I normally associate with Simak whose stories often seem Earth based even when interstellar travel occurs. Also Simak treated us to a science fiction trope, the trader in space that is common in the work of other authors but not necessarily in his. In his introduction to the story Wixon notes that when it was submitted to Galaxy the editor Gold,

"sent it back for revisions, but he also suggested that Cliff make a series of it and pledged himself to buy the series. Cliff did revise the story, and then started plotting a second “robot team” story—at which point Gold returned “Installment Plan” for more revisions, which Cliff provided within a week. But Cliff’s notes give no hint that he ever again thought of returning to the second tale. I like this story quite a lot, and it puzzles me that Cliff apparently did not … but then, he was not one to indulge in sequels."

Intro to "Installment Plan", I Am Crying All Inside: And Other Stories

Given how popular stories of traders in space, see Isaac Asimov's Foundation novels or Poul Anderson's Nicholas van Rijn stories for two examples it is interesting that Simak did not pursue this opportunity.

We can also see how uninterested Simak is in detailing how technology like FTL travel is achieved. The description of the propulsion of the cargo sleds may actually be the longest explanation I can remember Simak providing in any work I have read.

The robots here simply seem to handle it was a normal part of their duties. I think this is important more because it demonstrates that while the robots Simak has created are often similar, domestic servants are common, I don't think their attributes are necessarily consistent from story to story.

At present I would say the robots in "Installment Plan" are the most human of any Simak presents. They actually argue with and tease Sheridan as human coworkers would. They gamble as a form of entertainment, something I want to look at in more detail in another post. Two are critical of what one would assume is the rather basic spacehound transmog, Ruben says tired he is of it, while Lemuel notes how limited it is. One thing that just occurred to me (sorry) is that all the robots I remember from his stories seem to be identified as male. So in future reading I will try to understand what role if any gender plays in Simak's robots.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)